©2009 Evan Dorkin. From Dork #5 & Dork Volume 1: Who’s Laughing Now?. 98

©2009 Evan Dorkin. From Dork #5 & Dork Volume 1: Who’s Laughing Now?. 98

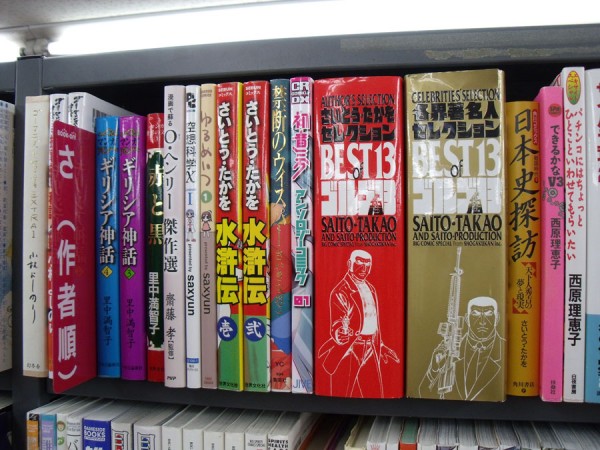

Random Japan: Bookstores

Book-Off in Kyoto. Frighteningly cheap books.

Casa Magazine Cover in an Osaka Bookstore. Featuring a lovely little colour Moomin illustration.

Osaka Bookstore– 21 prints magazine with a cover by and feature on Moyocco Anno.

Same bookstore. It’s another history book by Hideo Azuma, author of Disappearance Diary. Lots more to be released by this fascinating creator.

A brand-new 2-volume best-of of Oishinbo, focussing on Shiro and Yuzan. MAVERICK! TYCOON!

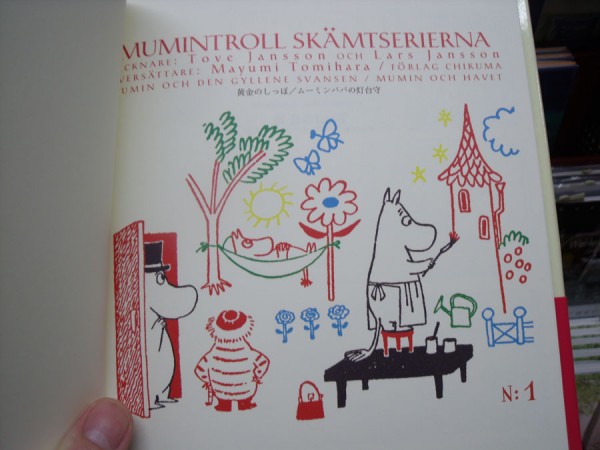

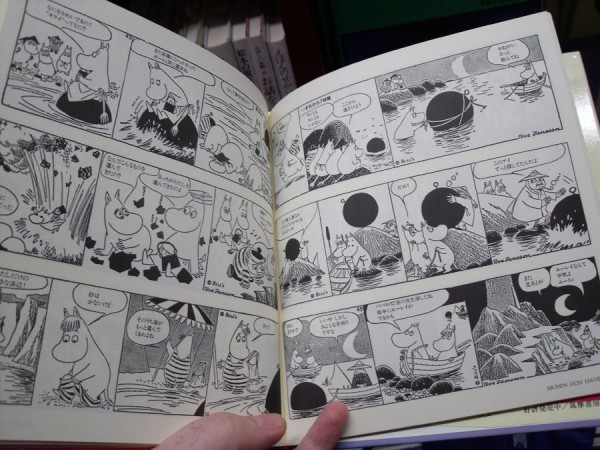

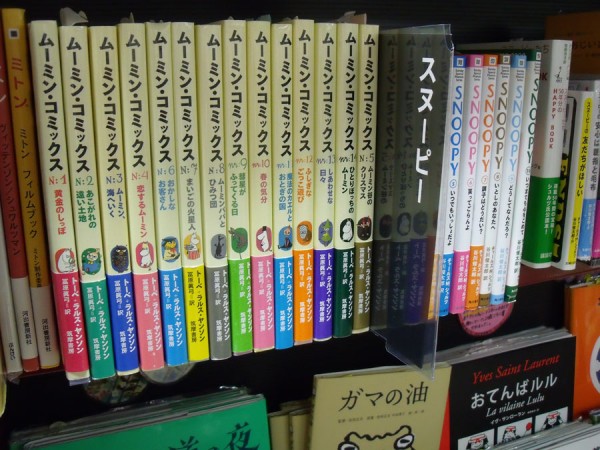

Tripped over the Japanese-language reprints of Moomin whilst there. Lovely, small little hardcovers. Let’s have a peak:

It’s a little funny to see the Moomin’s speaking Japanese… especially type-set Japanese.

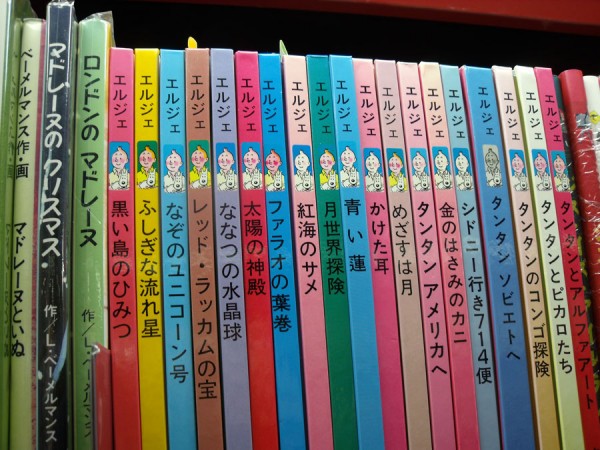

Another classic of comics literature… kept in the kids-book section rather than with the manga or comics.

Videogame strategy guides and artbooks. I spent a bit of money here.

I have no interest in Monster Hunter, but the art in this was lovely. 2 hardcovers in one package.

Monster Hunter is really popular in Japan.

I’ve got another big post in me on the manga sections of bookstores, for you bookstore fans. No worries.

– Christopher

Your Daily Dose of FUN: At Home With– The Grays

©2009 Evan Dorkin. From Dork #5 & Dork Volume 1: Who’s Laughing Now?. 97

©2009 Evan Dorkin. From Dork #5 & Dork Volume 1: Who’s Laughing Now?. 97

Random Japan: Kazuo Umezu Makoto-Chan

That’s a huge fucking cell-phone strap, let me tell you.

– Chris

Your Daily Dose of FUN: The Latchkey Kids!

©2009 Evan Dorkin. From Dork #5 & Dork Volume 1: Who’s Laughing Now?. 96

©2009 Evan Dorkin. From Dork #5 & Dork Volume 1: Who’s Laughing Now?. 96

Manga Milestones 2000-2009: 10 Manga That Changed Comics #8

8. The Push Man, and Other Stories, by Yoshihiro Tatsumi. Published by Drawn and Quarterly, September 2005.

8. The Push Man, and Other Stories, by Yoshihiro Tatsumi. Published by Drawn and Quarterly, September 2005.

Alternative Comics: The purveyors and creators of that material generally don’t prefer the work to be called “Alternative Comics.” It’s a term that necessarily sets the work in a context outside of mainstream acceptance–an alternative to what? Which means that, if you’re it’s an “alternative” comic, you can’t discuss it without discussing what it’s also an alternative to, which at least in the context of North American comics, means “Superheroes”. “Indy” generally doesn’t fly either, except for the very young. “Indy Comics” automatically conjures up notions of, again, working outside mainstream notions of form, or too-often, quality. Not-ready-for-prime-time. It also necessarily excludes “indy” work that comes from major financial backing. Is Dash Shaw or David Heatley “indy” when they’re self-published? When they’re pub’d by Fantagraphics? How about when those self-published comics are the collected by a division of mega-publisher Random House, are they “indy” then? It’s a weird label.

Most creators prefer, simply, to say that they make “comics”. No adjective necessary. But when pressed, the phrase that tends to cause the least bristling, to have found the most adherents amongst discerning comics connoisseurs, is “Art Comics.” Comics that are, and/or aspire to be, art, rather than merely existing as illustration, or commercial product. Comics are a mass-produced medium (for the most part), there’s always a tricky and prickly balance between art and commerce in every single book. Few authors have the luxury of their work appearing in print exactly the way they’d intended. Ware, Seth, Clowes, Spiegelman… Probably a dozen others working in the medium, in total. I hadn’t really heard the phrase “Art Comics” before I started working at The Beguiling, much like before I met my husband I hadn’t heard the phrase “Art Music” to refer to music that was not “pop” or, in the common vernacular, popular. Music as art, rather than music for an audience. Sometimes both. But I’ve grown to like the idea of it, all of us as readers forced to consider the intentions of the artist in the creation of work; the mere naming of the type of book a cause for critical examination. Art Comics. Ask for them by name.

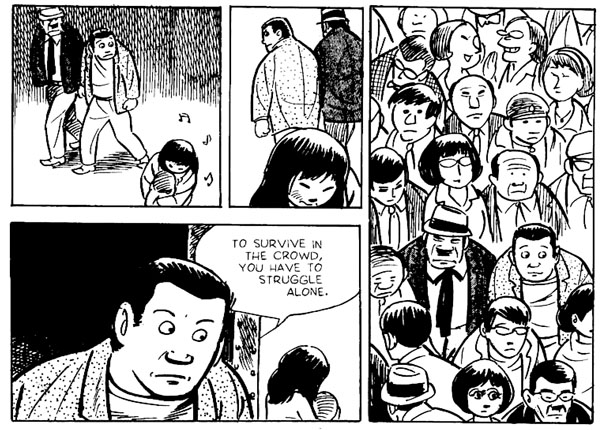

So then in 2005, after successfully releasing 15 years of art comics, Drawn & Quarterly released their first, and possibly the first, Art-Manga. Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s The Push Man and Other Stories is a collection of short works about everyday life in postwar Japan, and the heartbreaking and often horrifying mundaneness of living. It is “Gekiga,” a close-cousin to manga that came from the same place that the phrase Art Comics must: What if there’s a better way to tell better stories with words and pictures? What if instead of ‘irresponsible pictures’, as is one of the translations of the word manga, what if they made dramatic pictures (gekiga)? What if they strove for realism, maturity, experimentation, seriousness, and to touch the human soul? What if all of this ended up in direct contrast to the popular work of the time, but wasn’t a reaction to the work so much as simply being dissatisfied with artificial borders of the medium? What if manga could also be art?

Yoshihiro Tatsumi had been beaten to America’s shores twice before the arrival of The Push Man, and both times, by himself. Drawn & Quarterly had published one of Tatsumi’s shorts from The Push Man period, called “Kept” in 2003, in their fifth (and final) Drawn & Quarterly Anthology volume. Going back even further, an unauthorized English-language translation of a Spanish edition of Tatsumi short stories was published in 1988 by Catlan Communications. It was entitled Good-Bye and Other Stories, and until his first visit to North America, Tatsumi himself did not know it had been published.

The Push Man came to North America because of Optic Nerve creator Adrian Tomine. He’d owned some of the material, and ‘read’ some of the material, despite his inability to read Japanese. The storytelling in the work is marvelous, with layouts and framing designed to move you effortlessly through the story, except when it’s designed to give you pause. Tomine admitted to learning a lot from the work, declared that the books had reignited his interest in comics when he lost interest in superheroes, and that Tatsumi’s comics informed his own. Tomine pushed for years for material to be translated and brought to a wider English-language audience. That immediately set the context of the work for the readers who were going to encounter it for the first time; one of the most lauded art-comics creators in North America thinks that this guy, and this work, is the best in all of Japan. That’s a hell of a context to have the work released into, not just as a reader, but as a critic, as a bookstore buyer, as a bookseller. As a fan of Adrian’s.

Context is important, too. Labels like “Art-Comics” give a context to work, as I mentioned, but format gives a context too. If you’ve read a lot of manga, then you tend to think of manga not just as a collection of storytelling tics, or as work from a country of origin, or big eyes and small mouths, but also as a format. Tokyopop revolutionized format–book size and price point–and made the industry follow along. If you’re manga, then you’re 5.5″ x 7.5″, 200 pages, and $10, give-or-take. The book chains had further solidified that format, where covers needed to feature characters (no more than 2), and the characters needed to be looking right at the reader, and the logos had to be big and bold and easy-to-read from across the store. In 2005, manga was as much a product, a commodity, as it was a medium. But if you’re a Japanese comic and you come out in a 6″ x 9″ Hardcover, with a taped binding, monochrome covers, at $20? What are you then? Are you manga? Or something else? Are you gekiga? Art-manga? Or is just being “other” good enough for a first shot across the bow?

It’s important to note that the idea of art-manga had been tried before, and had even found measured success. Fantagraphics had released the excellent and inventive Anywhere But Here by Tori Miki earlier in 2005, and the alt-manga anthology Sake Jock in the 80s. Small publishers like BLAST! books had tried “alternative” manga in their anthologies like Comics Underground Japan. Viz had probably the most sustained success with their Pulp magazine and line of manga in the mid 90s and early 2000s, with a great selection of seinen (men-in-their-late-teens-and-early-20s manga) titles, and the occasional truly “mature” work like the early Jiro Taniguchi noir thriller Benkei in New York, or their groundbreaking release of Tezuka’s late-period masterwork Phoenix. 2005 had already seen Vertical’s Buddha from Tezuka, and the Nouvelle Manga movement that Fanfare was slowly rolling out on our shores, all around the same time, more or less. It should be said that the time was ripe for one big work to come out, to catch really pull the idea of Manga For Adults out of the ether and make it whole. Tomine put his reputation on the line to say that that book would be Tatsumi’s, and convinced D&Q to do the same.

I was incredibly excited at the prospect of its release, and in between the announcement of The Push Man and it arriving in stores, I even managed to track down a copy of the illicit Good Bye and other stories from Catlan. Reading those stories, I pretty much knew Push Man would be a hit.

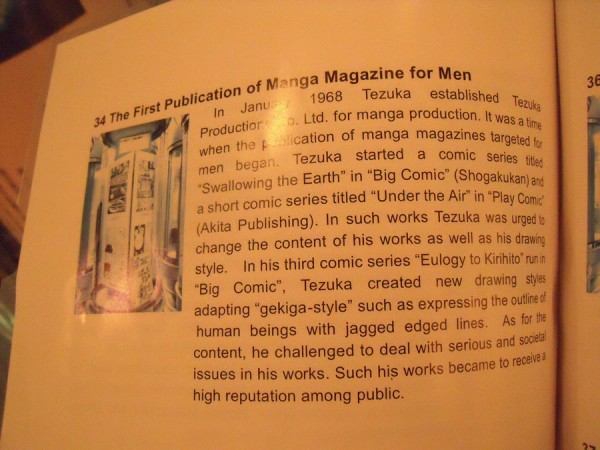

Now I’d like to share a photograph with you. I took it while I was at the Osamu Tezuka Museum in the summer of 2009. They have a little English-language hand-out guide that explains and translates each of the permanent exhibits. Here’s the section on Tezuka moving to Men’s Manga Magazines.

So let me parse that out for you. Gekiga, or gekiga-style comics, were the mature style of comics that the single-most-popular creator of manga adapted his style to, in order to tell his most mature and important works (including, as mentioned, Ode to Kirihito, which was serialized in Japan from 1970-1971). Tezuka started adapting Gekiga into his work in 1968, more than 10 years after Yoshihiro Tatsumi had worked with a couple of other authors to develop it. While the stories collected in The Push Man are all from 1969, Tatsumi had started telling these short, sharp, pictures of everyday Japanese life years earlier, and their success and innovation caused Tezuka to reinvent himself and create some of his finest works, including Ode to Kirihito, MW, and the later Phoenix stories. Tatsumi really was Capital-I important, with an enormous pedigree. All of this was either intimated or stated outright in the build-up to the release of The Push Man, but if the work hadn’t been any good, it wouldn’t really have mattered.

The September 2005 publication of Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s The Push Man and Other Stories was when Art-Manga arrived in North America. It elicited a strong critical reaction, but more importantly a sustained one, with reviews of the work coming all through 2005 and into 2006, when a second volume of Tatsumi shorts was released. The book was a sales success too; it’s currently in its third printing in hardcover. It found an audience.

The work was not fantastical in any way, in fact the stories seemed to be entirely without genre trappings or manga shorthand or idioms at all. Tatsumi’s 8-page shorts seemed to consciously reject what we would normally associate with manga in any way it could, Tatsumi telling his stories inspired by police reports or the daily news delivered with a brutal realism, an unflinching eye into the stark realities of urban living. Violent tableaux. But the craft! The craft of these stories is so, so high. They’re not just affecting but effective, with art that’s been developed and then paired down again to the most essential lines, shadows, and ideas. It’s manga that reads like It’s A Good Life If You Don’t Weaken or Louis Riel or Sleepwalking. It’s Drawn & Quarterly manga. It’s Gekiga. It’s Art-Manga.

Manga Milestone #5, the release of Tezuka’s Buddha, showed the world that manga could be for Grown-ups, and that it could tackle mature ideas. But it was still, at best, a hybrid book, created not just to engage an adult audience but also to stay friendly to a young one. It didn’t wholly succeed as a work for grown-ups because of its humourous asides and stretch-and-squash cartoon-influenced art. It used a fantastical storytelling style to tell a fantastical, epic story. What was so important about The Push Man is that it showed that manga did tell stories for adults, using realistic art, and straightforward storytelling. It showed that in addition to whatever we thought about manga, it was also about every day life, and it could be bleak and mean and gritty and funny just like life is. It showed that, beyond just being for grown-ups, manga could be literature too. But maybe most importantly, and this was right on the spine, it showed that some artists in Japan were treating comics like a mature, sophisticated venue for telling important stories, in 1969. Context.

To date Drawn & Quarterly have released 3 short-story collections by Yoshihiro Tatsumi, including The Push Man and Other Stories, Abandon The Old In Tokyo, and Good-Bye. Their most recent release is Tatsumi’s 845-page autobiography in comics A Drifting Life, which chronicles the birth of the manga industry, the creation of Gekiga, and Tatsumi’s development as a person and creator. Drawn & Quarterly plans to release one of Tatsumi’s earliest genre graphic novels, Black Blizzard, in spring 2010. There have been numerous other wonderful art-manga releases since The Push Man, that I am personally convinced have found a wider and more ready audience because of its release and its success.

-o+O+o-

– Christopher

You Are Listening To The Sound Of My Voice

So the manga milestones thing is going well, eh? Those last couple entries got pretty large and took a little more out of me than I was expecting. I need an editor. But yeah, the last 3 are sketched out and I should get to them tonight and/or tomorrow, wrapping the whole thing up.

What takes not-nearly as long as writing? Why just flapping my gums. I’ve recently been an invited guest on a couple of Podcasts, where I give my opinions on things without the luxury of an edit button. So far people seem to like them!

Back in December, right around the time of the kerfuffle about comics for kids (and don’t you worry, I’ll be revisiting THAT topic soon…), Dan Vado invited me onto the SLG podcast, alongside guest Evan Dorkin. You can find the archive of that Podcast here. I had been hopped up on energy drinks AND got on late, so the whole thing crackles with nervous energy, you should love it, Evan and I try not to feel bad about talking overtop one-another for a half hour. I think I end up on the podcast about 23 minutes in.

Meanwhile, my most recent podcast appearance was this past Friday. Canada’s SPACE tv network has a weekly podcast, The SpaceCast, and SPACE producer Mark Askwith(!) invited me on to talk about the decade in comics, particularly in and around genre comics. You can find that podcast right here. I had a really good time chatting with Mark, just shooting the shit about comics and graphic novels. I’m right at the beginning of the podcast and Mark and I chat for the first 30 or 40 minutes. I picked my favourite genre comic book of the last decade (ooooh!) and just talked about the stuff that really hit in the last decade… Almost none of which overlaps with what I’ve already written here at the blog. I’m followed by an interview with James Cameron, so that’s kind of weird. Edit: Just listened to the podcast… Pretty good in general, but I flubbed the details on http://graphic.ly/. Whoops…

Oh, and just big-ups to the dude who popped by Podcast-cherry, Robin McConnell at Inkstuds. I’m pretty sure I mentioned it at the time, but Robin, Dustin Harbin from HeroesCon/Heroes Aren’t Hard To Find, and myself talked inside-baseball retail nonsense back in October.

– Christopher

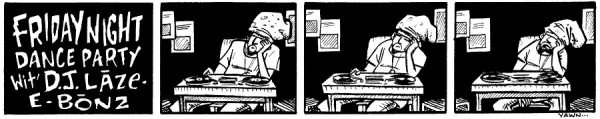

Your Daily Dose of FUN: Friday Night Dance Party…

©2009 Evan Dorkin. From Dork #5 & Dork Volume 1: Who’s Laughing Now?. 95

©2009 Evan Dorkin. From Dork #5 & Dork Volume 1: Who’s Laughing Now?. 95

Your Daily Dose of FUN: They’re Out There Somewhere!

©2009 Evan Dorkin. From Dork #5 & Dork Volume 1: Who’s Laughing Now?. 94

©2009 Evan Dorkin. From Dork #5 & Dork Volume 1: Who’s Laughing Now?. 94

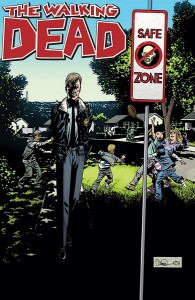

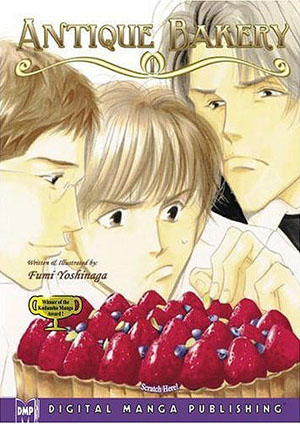

Manga Milestones 2000-2009: 10 Manga That Changed Comics #7

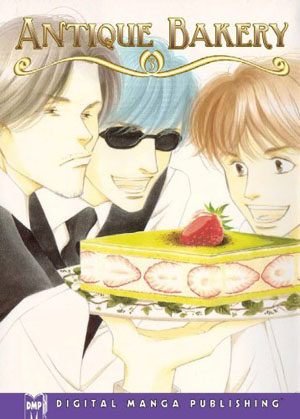

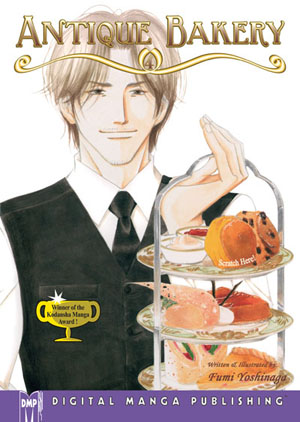

7. Antique Bakery Volume 1, by Fumi Yoshinaga. Published by Digital Manga Publishing, July 2005.

7. Antique Bakery Volume 1, by Fumi Yoshinaga. Published by Digital Manga Publishing, July 2005.

Much like Cardcaptor Sakura wasn’t the first shoujo title published in North America, nor the most popular, neither was Fumi Yoshinaga’s lovely, attractively-drawn episodic comedy/drama Antique Bakery the first yaoi title to make it to our shores or make it big. Actually, a very good case could be made by hardcore fans that, despite being created by an author known for her immensely popular yaoi titles and having come up through the doujinshi circuit and having gotten her start in yaoi, Yoshinaga’s Antique Bakery isn’t yaoi at all; just a male-centric shoujo romance story with a couple of gay characters. These people are, for my purposes, entirely wrong. Because however tightly you want to focus labels like yaoi, BL, ML, whatever, Antique Bakery was at the forefront of the then-exploding yaoi manga scene in 2005-2006, and Yoshinaga’s was the first book to cross over into mainstream comics and manga readership, and that makes it more notable and important than any series that could be considered a more authentic example of the genre. Antique Bakery made everyone sit up and take notice.

So lets get some terminology out of the way. I’m just going to copy the first couple of paragraphs of the definition from Wikipedia in here, because that way if anyone’s got a problem with the definition they can head over and edit it there, instead of bothering me about it:

Yaoi (????)[nb 1] (aka Boys’ Love) is a popular term for female-oriented fictional media that focus on homoerotic or homoromantic male relationships, usually created by female authors. Originally referring to a specific type of d?jinshi (self-published works) parody of mainstream anime and manga works, yaoi came to be used as a generic term for female-oriented manga, anime, dating sims, novels and d?jinshi featuring idealized homosexual male relationships. The main characters in yaoi usually conform to the formula of the seme (literally: attacker) who pursues the uke (literally: receiver).

In Japan, the term has largely been replaced by the rubric Boys’ Love (?????? B?izu Rabu?), which subsumes both parodies and original works, and commercial as well as d?jinshi works. Although the genre is called Boys’ Love (commonly abbreviated as “BL“), the males featured are pubescent or older. Works featuring prepubescent boys are labeled shotacon, and seen as a distinct genre. Yaoi (as it continues to be known among English-speaking fans) has spread beyond Japan: both translated and original yaoi is now available in many countries and languages.

Yaoi began in the d?jinshi markets of Japan in the late 1970s/early 1980s as an outgrowth of sh?nen-ai (????) (also known as “Juné” or “tanbi”), but whereas sh?nen-ai (both commercial and d?jinshi) were original works, yaoi were parodies of popular “straight” sh?nen anime and manga, such as Captain Tsubasa and Saint Seiya.

Excerpted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yaoi

So there you go. Yaoi, “Boy’s Love” (or BL for short), or shonen-ai. It all means about the same thing these days.

You may notice a bit of a chip on my shoulder about the definitions of yaoi, BL, shonen-ai, and what is or isn’t a representative of these genres, and that’s because the fans of these works tend to be the most intense and zealous out of any subgroup of fandom that I’ve ever personally run across. Yaoi is explicitly a fan-created culture, coming up out of the amateur-comics networks and meetings in the 1980s and in a very male-dominated society, and producers and proponents of this genre had to fight very hard to get taken seriously and treated fairly. I respect that, it’s hard not to, but considering its 2010 and the battles of yaoi and BL have been fought and won, here’s hoping that all involved can let their hair down a little.

One of the earliest manga to be released in North America that featured overt themes of same-sex attraction between male characters was the afformentioned Cardcaptor Sakura. The series featured several characters of near-deity status, and regular humans spending time with these deities would feel strange around them, a “tickle in their stomach” that was never explicitly refered to as romantic affection, but through context it was clear that characters would be in the initial stages of falling in love, and that happened a few times between male characters. The attraction was explained away (and of course those sorts of scenes were cut entirely from the anime release) and was never explicit, but it was quite surprising for fans at the time and it die-hard fans were wondering, from the moment it was announced as being licensed for North America in manga and anime format, if the homosexual overtones would be kept in. Tokyopop did, mostly. Nelvana didn’t, at all.

One of the earliest manga to be released in North America that featured overt themes of same-sex attraction between male characters was the afformentioned Cardcaptor Sakura. The series featured several characters of near-deity status, and regular humans spending time with these deities would feel strange around them, a “tickle in their stomach” that was never explicitly refered to as romantic affection, but through context it was clear that characters would be in the initial stages of falling in love, and that happened a few times between male characters. The attraction was explained away (and of course those sorts of scenes were cut entirely from the anime release) and was never explicit, but it was quite surprising for fans at the time and it die-hard fans were wondering, from the moment it was announced as being licensed for North America in manga and anime format, if the homosexual overtones would be kept in. Tokyopop did, mostly. Nelvana didn’t, at all.

As near as I can tell, the first yaoi titles published in North America actually came courtesy of ComicsOne all the way back in 2000. As part of their massive launch of titles, ComicsOne broke ground by not only offering the first real yaoi/BL/shonen-ai titles in English, but also by offering digital downloads of their work in Adobe E-Book format. They did that for all of their print manga, and also produced numerous titles that were download-only, including the yaoi titles, Lucky Star by Shimoi Kouhara, and Horizon Line by Ikue Ishida [2]. Personally, as a gay guy down on the availability of gay or even gay-themed comics in North America, and having heard the occasional rumour about Japan’s plethora of “gay” comics, coming across these unpromoted, strange-format (e-book only) books on the ComicsOne website was a little like finding gold in them-thar hills. Explicit gay romance comics, where unlike the works available at the time with gay themes like Banana Fish or X/1999 from Viz, no one was the victim of terrible violence or child molestation! Win-win! Of course, not having a credit card (nor trusting ebooks, really) I never got to read those works. But knowing that they were out there was enough, for me, at the time.

According to an article published by Marc McClelland, yaoi started to be licensed and published in North America in 2003, but he doesn’t cite any publishers or titles. Off the top of my head, I’m going to go ahead and say Tokyopop’s Fake, a buddy-cop drama with a frustratingly vague gay edge was first out of the gate. A quick Amazon search shows 4 volumes of Fake published in 2003, with the first out in May. Tokyopop would later release the other mega-popular fan-demanded yaoi hit Gravitation in August of that year, and between those two series would rule-the-roost, until 2004 when DMP would begin releasing their Yaoi Books line with Desire, Selfish Love, and my favourite Only The Ring Finger Knows, and CPM/BeBeautiful would explore the darker, S/M side of yaoi and BL releases with Golden Cain and Kizuna. From there, it was just a hop, skip, and a jump to Tokyopop’s dedicated yaoi line Blu, DMP’s dedicated “mature” line 801 and a rebranding of their titles to more closely associate themselves with the Japanese publishers, with the line switching from “Yaoi Manga” to “June Manga” (after the famous Japanese BL anthology). The success of yaoi in the marketplace, an honest-to-goodness phenomenon in a decade full of them (GAY PORN COMICS FOR WOMEN!) inspired a huge rush of publishers eager to make some money in this new market. Best of all, most Japanese yaoi publishers were smaller organizations, and much more independent, so while you could have industry leaders like Libre (who licensed to CPM) or June (who licensed to DMP), fledgling English-language manga publishers like DramaQueen, the Boysenberry Books arm of Broccoli Books, or the yaoi-arm of an established publisher like Media Blasters could still find great licenses to release. And that’s before you even scratched the surface of doujinshi.

By the time Antique Bakery was published by mid 2005, there were likely about 100 yaoi releases already. By the time Antique Bakery finished its 4-volume run in 2006, there were more than 200. That release schedule ballooned to, at it’s height, more than 20 yaoi releases in a month, every month. That segment of the industry was growing by leaps and bounds, and I’m gonna be honest, as alien as manga in general and the Toykopop revolution in particular may have seemed to most retailers, it didn’t have a patch on how out there even the idea of yaoi seemed, let alone the contents which were often out-and-out pornographic. (As an interesting side-note, there’s never been a controversy or freak-out over the contents of yaoi titles, despite some pretty explicit and questionable publications… I honestly expected one to come up by now.) But the most important thing was, yaoi sold. It sold like gangbusters. But with so much of it coming out, and so many of the series only a volume or two long (with almost no-effort on the part of the publishers to build a following for individual authors), most retailers, even bookstore buyers, had no idea how to buy the stuff past “give me everything” and putting it out on the shelves. Much like the first part of the manga boom though, that strategy only works when “everything” isn’t dozens and dozens of new titles each month.

By the time Antique Bakery was published by mid 2005, there were likely about 100 yaoi releases already. By the time Antique Bakery finished its 4-volume run in 2006, there were more than 200. That release schedule ballooned to, at it’s height, more than 20 yaoi releases in a month, every month. That segment of the industry was growing by leaps and bounds, and I’m gonna be honest, as alien as manga in general and the Toykopop revolution in particular may have seemed to most retailers, it didn’t have a patch on how out there even the idea of yaoi seemed, let alone the contents which were often out-and-out pornographic. (As an interesting side-note, there’s never been a controversy or freak-out over the contents of yaoi titles, despite some pretty explicit and questionable publications… I honestly expected one to come up by now.) But the most important thing was, yaoi sold. It sold like gangbusters. But with so much of it coming out, and so many of the series only a volume or two long (with almost no-effort on the part of the publishers to build a following for individual authors), most retailers, even bookstore buyers, had no idea how to buy the stuff past “give me everything” and putting it out on the shelves. Much like the first part of the manga boom though, that strategy only works when “everything” isn’t dozens and dozens of new titles each month.

What makes Antique Bakery important is that it’s a gateway book, and one that broke out of and above the crowd. It’s a gateway into yaoi, sure, but also into shoujo manga, and into manga in general. It’s about food and it’s about love, two very universal subjects that can hook even the most reluctant or unlikely of readers, and it did. It’s also a book that ended up, and I can’t figure out how, with the author at the forefront of the promotion. It may be that “Fumi Yoshinaga” is an easier name for North Americans to parse and remember, or it might’ve been the fan community that, through illicit scans and distribution, knew that Yoshinaga had a huge body of work and big career ahead of her, of which Antique Bakery was only the beginning. Or it might just be that it’s a great series, and her name is worth remembering for that alone. At any rate, when Antique Bakery was solicited somehow I’d been made aware that the author was Kind Of A Big Deal, and it seemed like DMP was doing a lot to push the series. For example, it was the first comic book since Ren & Stimpy #1 more than 10 years earlier, to feature a scratch-and-sniff cover. Each volume would have a new scratch-and-sniff, strawberries, chocolate, all meant to entice you into the baking world within. No manga publisher had done something that clever, to that point. It was pretty cool, and got people talking.

It occurs to me I haven’t described the series in much detail. Simply, it’s about a bakery run by an attractive, scruffy jerk who knows everything about pastries and cakes, and owns a bakery. The lead chef has been in love with him for 15 years, but the owner brutally turned him down. Throw in a reformed street-tough learning about baking, and a clumsy childhood bodyguard trained to become a waiter, and you’ve got a series of highly episodic chapters that extole the virtues of love, friendship, and delicious food. It’s light material (until the surprisingly intense final volume), a comedy-of-errors with romantic tension (gay and straight), shocking twists, and page after page of delicious-sounding and gorgeously drawn cakes and pastries. In short, it’s a fluffy, guiltly-pleasure of a book, incredibly easy and comforting to read, with genuinely deep characters and relationships. It’s like a network dramedy, crossed with a Food-Network special. It’s fun stuff.

From its description I can imagine many of you who haven’t read it (or any yaoi/BL/shoujo for that matter) couldn’t imagine how this could be good, or important. Well the pedigree of the book might convince you. The series won the 2002 Kodansha Manga Award for shoujo manga upon its original release, and the English edition of Antique Bakery was nominated for a 2007 Eisner Award for “Best U.S. Edition of International Material – Japan,” the award’s inaugural year. This book connected with people, and as the Eisner nom evidences, not just the small, vocal yaoi fanbase. It’s a highly-crafted work that received tons of reviews and great word-of-mouth attention online and in the fan press. The last three volumes of the series were short-listed for the inaugural 2007 list of Great Graphic Novels For Teens, put together by the Young-Adult Library Services Association (YALSA). The books received multiple printings, though unfortunately later editions were no longer Scratch ‘n’ Sniff. Almost from the month it was released, Antique Bakery became the poster-book for the Yaoi boom in bookstores and forward-looking comic shops across North America. It was a book you could hold up and say “This is yaoi! And it’s GREAT!” and not have anyone who flipped through it after you said that call you a liar and/or blush. Sure, in the end it might not be 100% accurate, it might not fall under the very stringent ‘rules’ of what constitutes a ‘yaoi’ or ‘BL’ title, but it acted as many readers’ first exposure to the genre, it got wide acclaim, and its really really good. It’s important to have gateway books, particularly for audiences that had been completely ignored by comic publishing for more than 30 years–women and gay men. I know more than a couple of each who hold Antique Bakery amongst the favourite comics of all time, and in the big picture I think that’s a lot more important than labels.

From its description I can imagine many of you who haven’t read it (or any yaoi/BL/shoujo for that matter) couldn’t imagine how this could be good, or important. Well the pedigree of the book might convince you. The series won the 2002 Kodansha Manga Award for shoujo manga upon its original release, and the English edition of Antique Bakery was nominated for a 2007 Eisner Award for “Best U.S. Edition of International Material – Japan,” the award’s inaugural year. This book connected with people, and as the Eisner nom evidences, not just the small, vocal yaoi fanbase. It’s a highly-crafted work that received tons of reviews and great word-of-mouth attention online and in the fan press. The last three volumes of the series were short-listed for the inaugural 2007 list of Great Graphic Novels For Teens, put together by the Young-Adult Library Services Association (YALSA). The books received multiple printings, though unfortunately later editions were no longer Scratch ‘n’ Sniff. Almost from the month it was released, Antique Bakery became the poster-book for the Yaoi boom in bookstores and forward-looking comic shops across North America. It was a book you could hold up and say “This is yaoi! And it’s GREAT!” and not have anyone who flipped through it after you said that call you a liar and/or blush. Sure, in the end it might not be 100% accurate, it might not fall under the very stringent ‘rules’ of what constitutes a ‘yaoi’ or ‘BL’ title, but it acted as many readers’ first exposure to the genre, it got wide acclaim, and its really really good. It’s important to have gateway books, particularly for audiences that had been completely ignored by comic publishing for more than 30 years–women and gay men. I know more than a couple of each who hold Antique Bakery amongst the favourite comics of all time, and in the big picture I think that’s a lot more important than labels.

Since Antique Bakery, DMP have published a number of additional books by Yoshinaga including Solfege, Ichigenme… The First Class Is Civil Law Volume 1 & 2, Garden Dreams, Flower of Life Volumes 1, 2, 3, & 4, The Moon and Sandals Volume 1 & 2, and Don’t Say Anymore Darling, with All My Darling Daughters scheduled to arrive in 2010 Edit: AMDD will be coming from Viz, not DMP. Tokyopop added Yoshinaga to their roster via their BLU yaoi line, with her series Gerard and Jacques Volumes 1 & 2 and the short story collections Truly Kindly and Lovers in the Night. Yoshinaga’s highest-profile release in North America came late in 2009, with the release of Ooku: The Inner Chambers Volumes 1 & 2 published by Viz. Ooku is an alternate-history series about early Japan, where women become the ruling class after a plague wipes out most men. The series is Yoshinaga’s most popular and best-received to date, winning numerous prizes including the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize for manga, 2007, shared with Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s A Drifting Life. FWIW my favourite of Yoshinaga’s works so far is Ichigenme…, a sexy series that really rings true as both a yaoi series and contemporary gay fiction. It’s filthy, too.

Images Top-to-Bottom: Antique Bakery Volumes 1-4, by Fumi Yoshinaga, published by Digital Manga Publishing.

-o+O+o-

– Chris