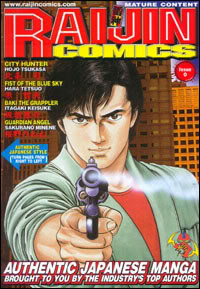

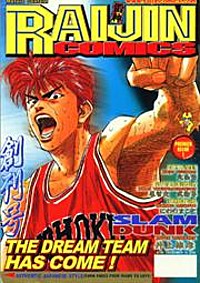

#6: Raijin Comics #46, by various. Published by Gutsoon Entertainment, July 2004

Upon the publication of the last issue of Raijin Comics, issue #46, in July of 2004, publisher Gutsoon Entertainment posted the following message to their website:

Dear RAIJIN COMICS readers,

Thank you for your enthusiastic support of RAIJIN COMICS. Over the past 18 months, we have tested the market to see how well a weekly and monthly manga magazine would fare with an American audience. Based on our research with readers, retailers and distributors, we have come to a conclusion – our publications, though appreciated by hard-core manga fans, are not penetrating a larger market.

In order for us to reach a broader market, RAIJIN COMICS, RAIJIN GRAPHIC NOVELS, and MASTER EDITION will be placed on hiatus for the time being. We will be taking time out to come up with ways to broaden the appeal of our publications, retooling stories and overall editorial content. RAIJIN COMICS Issue 46 and the June GRAPHIC NOVELS will be the last issue you will be printing.

All of our subscribers will be recieving a refund for the remainder of your balance with in the next few weeks. We are refunding you $3.95 for each issue owed after issue 46. For example, our charter members will receive a total of $7.90 for issues 47 & 48. You can see how many issues you had left by going to www.raijincomics.com and clicking on “my accounts”. Should you have have any questions and/or concerns with the amount, please contact our customer service department by e-mailing reimbursement@gutsoon.com or by calling 1.877.GUTSOON M~F from 10:00~ 7:00 PST.

Please note that the phone number and e-mail listed above are for orders and reimbursements only. To contact / comment regarding RAIJIN COMICS going on hiatus please e-mail raijinreaders@gutsoon.com

Again, we want to thank you for your support over the last 18 months, and look forward to the possibility of bringing you a more powerful, exciting RAIJIN COMICS in the near future.

Sincerely,

Horie Nobuhiko

PublisherMichael Andres Palmieri

Executive Vice President

But there would be no reprieve or relaunch, the possibility of Raijin Comics or publisher Gutsoon returning never occurred. To anyone involved or anyone in the know, this was not surprising at all… but it did mark the first real failure of the manga boom of the 2000s.

Let’s go back about 2 years from that date, to the summer of 2002. Thanks to Tokyopop’s phenomenal bookstore success and some agressive moves by Viz, the field for translated Japanese comics–manga–began to open up considerably in North America. Sure, stalwarts like Tokyopop, Viz, and CPM had been producing material solidly for years at that point. But the rising awareness and success of manga, coupled with the virtually limitless supply of material that was available in Japan–literally MILLIONS of different series–inspired a number of new start-up companies and organizations. ComicsOne, a California-based publisher licensed a broad array of different manga, possibly one of the most eclectic line-ups of material in the business, including comedy works like Crayon Shin-Chan, Horror from Junji Ito and his three Tomie collections, historical fiction in the form of the full-colour Joan of Arc manga Joan, and then balanced it all by rescuing the licenses for popular Hong Kong action manhua. Studio Ironcat had been around for… a while (I honestly have no idea how long) and were just soliciting the first collection of the popular webcomics trip Megatokyo. Popular anime publisher ADV was about 6 months away from the start of their manga line with titles that either inspired or were based on their popular anime, and had started making very obvious rumblings in that direction, with early titles already solicited. The success of manga had not gone unnoticed, and things were really starting to heat up.

That summer of 2002 saw the press release in Japan about Shueisha partnering with Viz to do an American version of Shonen Jump. Shortly thereafter, a company largely comprised of ex-Shonen Jump cartoonists named COAMIX announced their intention to do a magazine in North America as well. Led by former Shonen Jump Editor in Chief Nobuhiko Horie and City Hunter creator Tsukasa Hojo, COAMIX got some funding together from both sides of the pacfic, and formed the company GUTSOON, to publish manga in North America. Like the Japanese Shonen Jump, their magazine would be weekly, and include a little bit of lifestyle content, and because the titles that they contained were popular in Japan, of COURSE they’d be popular in North America. They’d beat Shonen Jump at their own game! Out of this came Raijin Comix. A 200 page weekly manga anthology with cutting edge weekly video game news of japan, 16 pages in full colour. A big part of the initial investment in the magazine came from video game system manufacturer and game publisher SEGA, who were looking for an “in” to North American culture to give them an advantage in the video game console wars (Between Sega’s Dreamcast, Nintendo’s N64, and Sony’s Playstation). Already you can see that Raijin, as much as it attempted to sell the product, it also was trying to very ambitiously sell the lifestyle that went along with it. It’s important to note that this is the exact tactic that Shonen Jump used as well, though they employed many more partnerships, and their ace-in-the-hole was getting on TV in a prime spot, right from the get-go.

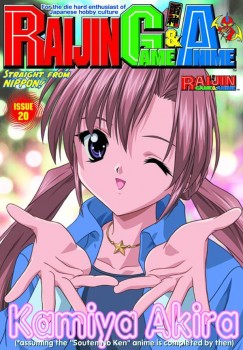

Once it was announced that Raijin was launching in North America, well, I have to admit I was personally pretty excited. A weekly manga magazine! It was everything I wanted from the manga boom–mature titles delivered at a fast pace, at a decent price-point. What gave me pause even then, though, was that the magazine was undergoing significant format changes after its announcement, and it seems like all of the format changes came at the request of one of their biggest partners, Diamond Comics Distributors. Between their initial announcement and solicitation, Diamond managed to talk them into a massive format change, with the video-game content being spun off into a separate magazine, known initially as “Fujin” but then retitled “RGA” (Raijin Game & Anime) between solicitation and its arrival in stores. RGA ran a buck an issue, came out on the same weekly schedule as Raijin, and was sold in bundles of 10 that direct market retailers could buy separately. This would get the price of the weekly magazine down to $4.95 (the same price as Shonen Jump) from its initially planned price of $6.95. They also begged–BEGGED-Raijin not to do a weekly magazine, as Diamond, frankly, isn’t very good at distributing weekly product. But when the core fundamental of your business plan is “be there every week”, well, there are some things you can’t change. I think the first missed-ship week came 17 weeks in, with 2 issues shipping on the following week. All of it Diamond’s fault of course, but when you’re not a big front-of-catalogue publisher, there’s only so much attention that they can give your work.

I had been retailing comics, more-or-less constantly, for about 6 or 7 years by the time Raijin was almost ready to drop in North America. I had ordered and sold the very first Tokyopop products, and seen the steady rise of interest and sales in manga. I was as much of a retail expert on manga as anyone could be, at that point, at least in the direct market, the network of comic book specialty stores where (then) the vast majority of comics sales were made. And I was mouthy on the internet, particularly the extremely popular Warren Ellis Forum, and so I was sought out by a good, well-meaning dude from Raijin to bounce some stuff off of me. I was flattered (who wouldn’t be?) and I gave my advice freely and openly. Not all of it was listened to, but in the end (and almost entirely uncredited) there’s a lot of me in Raijin magazine.

As I mentioned during the entry on Shonen Jump, the initial chapters of manga are often much longer than the standard chapters, and so it took the first 3 issues of the magazine to serialize all of the “launch” titles of the work. So on that note, the titles that “launched” in Raijin were: The hyper-violent The Fist Of The Blue Sky by Tetsuo Hara, the sequel to The Fist Of The North Star; the first sports-manga translated into English, Slam Dunk, by Takehiko Inoue; the ultra-80s action/sex/comedy police series City Hunter by Hojo Tsukasa; the over-the-top violent action/ecchi series Bomber Girl by Makoto Niwano, a series so borderline-porn that its sequel was just all-out actual porn (and thus never released in North America); the ultra-violent underground fight-comic Baki The Grappler by Itagaki Keisuke; the surprising and mature contemporary political fiction series The First President Of Japan by Yoshiki Hidaka and Ryuji Tsugihara; and Guardian Angel Getten by Minene Sakurano, about a boy and a guardian angel that’s could charitably be described as “regurgitated”. The slogan on the first issue said, The Dream Team Has Come!, which I hope helps you understand the massive hubris and ego involved in this project… These guys really thought they were bringing the greatest manga in the medium to North America, and that success would greet them warmly.

The Dream Team, by the way, was very very manly, from the manliest period in manga history (the mid 80s and early 90s), and The Dream Team arrived at a time when the most popular manga in the industry were 1. Pokemon, 2. Sailor Moon, 3. Dragon Ball, and 4. Cardcaptor Sakura. Right off the bat, you can see that this unique, innovative, product was going to be swimming upstream, right? Well compound that with the fact that the magazine was going to be printed (much like Shonen Jump USA) entirely right-to-left in the Japanese orientation. A handy rule of thumb that we’ve learned in manga, particularly in publishing, is that the older the intended audience of a translated work, the more likely it should be “flipped” into the North American orientation, because old people hate learning new things. Raijin was a pretty-firm 16-and-up kinda magazine (and frequently even a little bit more violent/sexy than that), at a time when manga was finding a new, YOUNG audience. Even amongst the most popular fighting manga, the differences between Raijin and its competitors would be pronounced; in Dragonball Z when one character punched another, they’d go flying through the air, maybe knock down a mountain, maybe even spit a little blood, but then get back up and give as good as they got. In The Fist of the Blue Sky when a character got punched, his head exploded. It was for grown-ups, grown-ups who were going to have to essentially learn another language. American grown-ups.

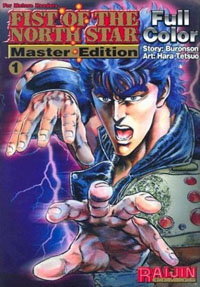

That’s the other big thing about the magazine: It was called Raijin Comics. Not Raijin Manga. Or even just “Raijin”. Raijin was not aimed at manga fans in North America. It was aimed at “comics” fans, the folks reading superheroes primarily. It took the message of Tokyopop–that Western fans are more open to manga now–and decided that meant publishing manga explicitly for existing comics fans, who were male, 18-49, and white. Don’t believe me? I’ve got a great anecdote for you: Fist Of The North Star co-creator Tetsuo Hara was (and is) convinced that his landmark series is one of the greatest of all time. All. Time. It’s a post-apocalyptic fantasy epic where dudes hit each other until they explode, and women are cann0n-fodder… at best. It’s not without its over-the-top, head-punchy charms, but… But Hara isn’t hearing that of course. He was (reportedly) very unhappy by the series’ first sojourns to North America, where the anime tv series was cut to hell and repackaged as a movie, and where the manga was released small, and flipped, and incomplete. He became convinced that the hideously violent and misogynistic series could be a success in North America if only it were printed bigger, and in colour. So at a time when manga was finding massive, massive success by going as small and cheap as possible, Hara decreed that North Star would be big, bigger even than North American comics (that was an important part, bigger because his work was better), with brand new digital colour and on nice paper, in the original Japanese reading method… at a cover price of $18 a volume. He had produced a classic, and he wanted it to compete with American classics, despite the fact that American Superhero Fans are more-or-less finding what they want out of American Superhero Comics, and that the entire industry was going a different way, building a new audience and not relying on selling more product to the old one. They managed to crank out 9 volumes of the remastered North Star in the 18 months they were in business, but it’s safe to say it did not set the manga world on fire. Neither fish-nor-fowl, the series didn’t look like popular manga, it was in colour and expensive making it weird and inauthentic for the die-hard manga fan, and superhero fans? Well, let’s just say that they’re still not entirely sold on buying “original graphic novels” almost 10 years later. This is just an anecdote, like I said, but its emblematic of the entire problem with Raijin; it was a grand, important vision for specific manga works appearing in North America, that absolutely could not see the forest for the trees.

The magazine failed. Slowly, surely, it failed. The calls from the folks at Raijin asking for advice got longer, and especially towards the end, my suggestions for the magazine were being incorporated fast and furious! The addition, at the end, of Japanese language lessons via manga? Me. With cheap trades coming out right on the heels of the serialization, they needed a reason, any reason, for folks to pick up the magazine, and material that wouldn’t be collected was it. I might’ve even been the one to suggest more short, one-shot manga that would be a satisfying read for someone picking up the magazine and not just getting stories mid-way through their serialization, which they did with the mountain-climbing manga they had…. But anyway, the magazine flailed, mixing manly manga with vague pseudo-porn, a couple of strong features, and then in a last-ditch-effort to attract the still-burgeoning audience for much younger shonen and shoujo manga, adding the treacly-sweet “Bow Wow Wata” shoujo series into the magazine… right next to hyper-violent Baki The Grappler and the terrorist action manga Revenge of Mouflon. I’d ask, rhetorically, “What the hell were they thinking?” but I know what they were thinking: “Make the magazine more attractive to the new manga fans, so that they’ll discover that the manga we’re publishing is SO MUCH BETTER!” Seriously. 20-year old action manga was simply waiting for fans of Fruits Basket to discover it.

Oh, I should fill in some of the gaps for you here. In addition to a weekly magazine, Raijin Comics, the 16-page videogame and anime suppliment RGA, and the bimonthly release of Fist of the North Star in colour, publisher Gutsoon began to release Tokyopop-sized, black and white collections of the manga serialized in Raijin Comics for just $9.95 a book. They were, unsurprisingly, pretty popular, fitting in nicely with the masses and masses of other manga being released at the time. Solid, respectable sales in the bookstores, by my recollection, and we did fairly well with them at The Beguiling. In individual collected form, the diversity (and honestly, the strangeness) of a line comprised of older-shonen and seinen manga on a variety of subjects? Well that was a strength, as new audiences that weren’t being served by the onslaught of contemporary shonen and shoujo material could find something more to their tastes, whether that was over-the-top action manga or a political thriller, without being subjected to Getten, Bow Wow Wata, or Bomber Girl. Or vice versa, I suppose? It was no Tokyopop revolution, or anywhere near the staggering sales and tie-in popularity Viz was receiving from Shonen Jump magazine, but it was their first real success.

I will say that the most realistic part of their business plan was that they anticipated a weekly circulation of approximately 15,000 copies, which was not unreasonable, particularly in hindsight when Shonen Jump launched with a circulation of over 300,000 copies of the first issue. 15,000 copy sales would’ve placed them in the same neighbourhood as CrossGen. Presumably at least, they had worked out a way that they would be profitable on a weekly circulation of 15k. According to the sales that I can find, issues 5-8 of the series averaged a sell-in of about 2100 copies through Diamond, coming in very near to the bottom of the top 300 sales chart that Diamond publishes every month. Shonen Jump’s first issue came in at around 8500 copies through the direct market, a far, far cry from its total sales. Raijin’s staff at the time touted their victory over SJ during their respective first months, because the combined sales of all 4 weekly issues beat the first-issue sales of Shonen Jump. Spin is a powerful thing, and at that point, they needed whatever they could get. I should be fair and say that they did have a newstand presence and a subscription base, but as evidenced by their going-out-of-business letter at the top, apparently neither of those numbers were anything to crow about.

Sales declined as the months wore on. RGA lasted 20 issues (and 20 weeks) before being folded back into Raijin. In October of 2003, the magazine went from a weekly to a monthly (with no commensurate increase in size but a new cover price of $5.95, a buck more than its closest competition or its previous pricepoint). The last weekly issue of the magazine, #36, seemed to come in at about 1500 copies through Diamond, and from #37 it didn’t appear to chart in the top 300 whatsoever.

The last year of Raijin, I honestly don’t know that much about it. I’d lost touch with most of the people involved, and it was clear that no one was having a good time of it there. Worse, it became pretty clear that they really didn’t seem to know what to do, and despite a huge launch budget and lots of bravado, maybe they never really did. Their perceived strengths when launching became hindrances, particularly being tied to a monthly magazine format that hamstrung their graphic novel program, that needed material released quickly in order to solicit the (to my knowledge) profitable trade program. I don’t think it ever occurred to anyone involved with the magazine that it wouldn’t be a huge success, given the stunning popularity of the core titles Fist, City Hunter, and Slam Dunk. Raijin and Gutsoon’s greatest failings, aside from hubris, was an inability to adapt to a marketplace undergoing a massive change and, considering how much _they’d_ changed their plans in the 6 months between announcing the book and the first issues arriving on stands, you woulda thought that change would be one of their biggest strengths.

The serialization of Raijin Comics ended with the 46th issue. It came out a few weeks late, and then the company disappeared. While a few trade paperbacks did manage to make it to store shelves past the end of the monthly magazine (basically, anything that was already at the printers), Raijin Comics #46 marked the end of Gutsoon, and was the first real casualty of the manga boom. True to their word though, they behaved honourably towards their subscribers and sent them cheques for the remainders of their subscriptions, and did their best to close up shop neatly and cleanly.

In the years that followed, many [overly] ambitious publishers would crash and burn. The biggest was probably ADV Manga, a subsidiary of anime publisher AD Vision. With a stunning amount of hubris, the company which had, to then, released a number of moderately-successful titles tying-into their anime line decided to up the ante considerably in 2004, releasing dozens of brand-new and largely mediocre anime-tie-ins and various manwha titles, all in the space of just a few short months. Tokyopop and Viz had ramped up their lines considerably, releasing over a dozen manga a month, each. ADV emulated their output but not any of their acumen (or years of gradual building), and basically dumped tons of product onto the market with no support or foresight. They were convinced, somehow, that manga was a license to print money. It didn’t matter if it was a good manga, like Tactics, or a bad manga, like First King Adventure, it was just dozens of first and second volumes dumped on already straining-at-the-seams bookstore and comic shop manga sections, and something had to give. Most of their line was cancelled after 1 or 2 volumes at the end of 2004 and the beginning of 2005; ADV re-launched in 2006, only to stop publishing entirely by the end of 2008. Companies like Be Beautiful, DramaQueen, Broccoli, Dr. Master, Infinity, and more splashed onto the scene and then disappeared completely in the past decade, and industry stalwarts like Tokyopop suffered through some tough times, with Every Single Person I Know In The Industry predicting their imminent demise, monthly, if they offered any opinion at all.

In writing this I tried to remove myself a little from the proceedings, and view the history of Raijin through press releases, reviews, message board chatter, and more, as much as from my own remembrances of the time. But I’ll own up to the fact that, despite everything, I was pretty close to the situation and didn’t have the warmest feelings for Raijin Editor Jake Tarbox towards the end (or afterwards), and that this entry out of all of them could be the closest to flat-out wrong. But until proven otherwise, this is what went down with North America’s first and only weekly manga magazine 7 years ago, one of the biggest launches I’ve ever seen, and one of the most spectacular publishing failures I’ve ever witnessed. To Raijin: It would’ve been nice if more publishers had learned from your mistakes.

Other Resources:

Raijin Archive at AnimeNewsNetwork: http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/encyclopedia/manga.php?id=2016

Raijin Comics Website (Wayback Machine): http://web.archive.org/web/20040626023411/http://www.raijincomics.com/

-o+O+0-

Coming soon! Parts 7, 8, 9, and 10.

– Christopher