#3: Shonen Jump #1. November 2002. Published by Viz.

I kept going back and forth on this one, trying to decide whether November’s Shonen Jump Volume 1, Issue 1, was more of a milestone than Raijin Comics #1, released a month later. In the end, Raijin was an innovative and exciting product, but it’s most notable for failing. Shonen Jump is still going strong 8 years later, with a monthly circulation of 200,000+ readers. So let’s talk about Shonen Jump instead.

In November of 2002, the industry was not exactly hurting for manga anthologies. In Japan, anthologies are plentiful–it’s very rare for a work to be released in a long-form edition without having been serialized first. In fact hundreds of different series are serialized in different magazines each year, and the king of the heap with the highest circulation is Weekly Shonen Jump. While Tokyopop had got its start in the anthologies MIXX, SMILE, and TOKYOPOP, and Viz had Manga Vizion and my beloved Pulp, by the end of 2002 all of those magazines had bitten the dust. Sure, Dark Horse’s Super Manga Blast and Viz’s own Animerica Extra continued to bring manga to the masses with their 100 page, $8 price points, but the industry was headed a different direction. With the popularity of the smaller, cheaper manga that Tokyopop was pushing (and Viz had yet to embrace…), and Tokyopop’s then-recent decision to end serialization of most of all of their comic books and go straight-to-trade, combined with Dark Horse announcing that it was going to be releasing Tezuka’s Astro Boy as a series of graphic novels at that same $9.95 price point, it looked like the sun was finally setting on serialized manga.

But. In June of 2002, Viz announced that it would be partnering with Japanese publishing giant Shueisha to bring their flagship manga anthology, Shonen Jump, to North America. It flew in the face of the newly burgeoning market. While Viz had experience publishing anthologies at this time, it was seen as a bold–even wrong-headed move by most. Particularly as Viz’s version of Shonen Jump would be monthly, and Shueisha’s was weekly. Fans decried the pacing, saying that favourite series like Naruto and One Piece would lag further and further behind their Japanese serializations (of, if only they knew…). And who needed anthologies anyway, why not just go straight to the collected edition?

The reasoning was pretty obvious. Viz was going to use the strongest tools in their arsenal, the absolute biggest and most popular manga in Japan, to make an offensive outside of the comic book distribution system into… well, everywhere else. They anchored the book with the still incredibly popular Dragonball Z. They partnered with The Cartoon Network, filling the book with series that also had anime airing on TV (or were about to!). They had Yu-Gi-Oh, the manga that inspired the hit collectible card game, and they bound a rare card in the first issue to goose sales. They worked their asses off to get it good distribution, working well-ahead with Diamond and (the now defunct) Suncoast media stores, where tons of manga was already being sold. They got great newstand presence too…!

All of that added up to first issue-sales of over 300,000 copies, which effectively silenced all those critics I mentioned in the preceding two paragraphs.

First chapters of manga are usually double-sized, 48 pages or so, to give readers a more thorough introduction to the story. Because of this, the first issue of Shonen Jump only featured 5 of its planned 7 “launch” series, Akira Toriyama’s Dragonball Z and Sand Land, Yoshihiro Togashi’s YuYu Hakusho, Echiro Oda’s One Piece, and Kazuki Takahashi’s Yu Gi Oh. The second issue introduced the world to Masahi Kishimoto’s Naruto, and the third issue gave the world Hiroyuki Takei’s Shaman King. Within 3 months, the official launch line-up of Shonen Jump was completed. If you look at the titles there, more than half of them were amongst the most popular and bestselling manga of the past 10 years. Naruto and One Piece still top the charts. All in one magazine.

The kicker? Shonen Jump magazine was available every month, on every newstand, more than 300 pages at a go, for just $4.95. It immediately changed the game for manga pricing, but was also massively successful in attracting superhero readers like John Jakala, who published this infamous blog post, which I have reprinted in its entirety:

The Weak American Conversion Rate

After the last couple long posts, I figured I’d do something light. So here’s a comparison of what $60 will get you in manga versus American comics:

Gee, I wonder why young kids are flocking to manga?

(In case you’re wondering, that’s 12 issues of Viz’s manga anthology Shonen Jump (with a $4.95 cover price) on the left and 24 issues of various American comics at $2.50 a pop on the right .)

– John Jakala, October 30th 2003

It’s even worse now that American comics are $3.99 a pop. Funnier though; that stack of comics would be half that size.

Viz had beaten Tokyopop at their own game, and produced much, much-better looking material doing it. Granted, it accomplished this through massive investment by the largest publishing company in Japan, investment that eventually led to Shueisha and rival pub Shogakukan purchasing Viz outright… and man was that a game-changer or what? It allowed for a massive reinvestment in their line, huge expansion, and a radical shake-up of a company that had advanced only very incrementally over its time in the publishing game. And THAT came out of Shonen Jump too.

So lets see, our milestone has opened up hundreds of new outlets for manga sales, introduced tens of thousands of new readers to the medium of comics (manga), become the best-selling comic book since the speculator boom (and bust) of the early 90s, and was the first step to Viz being the publishing juggernaut it is today. Not too shabby. It also ended up inspiring the similar just-for-girls anthology Shojo Beat a few years later, putting comics explicitly for girls and young women back onto the newstand, from which they’d been absent (save Archie…) for years. Sadly, Shojo Beat was cancelled in 2009, but the trade paperback line that bears its name is still going strong, with some of the bestselling manga in the industry published under the Shojo Beat banner.

-o+O+o-

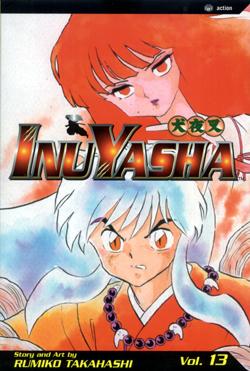

#4. Inu Yasha Volume 13, by Rumiko Takahasi. Published by Viz. April 2003. Solicited January 2003.

Then, one day, right in the middle of their serialization of the very-popular Inu Yasha graphic novels, Viz changed the format of their manga. Inu Yasha Volume 12 was the standard 6″ x 9″ format Viz manga had been using for years. It also retailed for $15.95, $6 more per book than a comperable series from another publisher. Then the next volume was completely different. It was terrifying.

By April of 2003, Tokyopop had given up on single issue comic books AND anthologies altogether, and increased their manga trim size to the now-standard 5.5″ x 7.5″. They were going straight to graphic novel format with shoujo series like Cardcaptor Sakura, Happy Mania, Marmalade Boy, and Tokyo Mew Mew, shonen manga like Cowboy Bebop, Dragon Knights, Luipin III, Rave, and Rebound, and even Seinen (young men’s) manga like Chobits and Initial D. In April of 2003 Tokyopop released 12 volumes of new material, par-for-the-course for them. A new publisher named ComicsOne has also released a bunch of manga in “The Tokyopop Format”. Dark Horse serialized Astro Boy trade paperbacks in “The Tokyopop Format”. And just like that, an entire trim-size of book became named after one company, and it stayed that way through most of the decade. The Tokyopop Format.

(Interestingly, the Tokyopop format doesn’t actually correspond to any sort of page size used in manga in Japan, or any size ratio. It’s actually a really awkward size for publishers, too long and thin for the original manga pages, which means that either more artwork gets chopped off on the sides, or there’s blank-space on the top or bottom, or the artwork is “smushed” to fit.)

When Viz announced that they were moving all of their books to a new trim size, they never came right out and called it “The Tokyopop Format”, they couldn’t, but yeah, they lost that particular battle.

But when Inu Yasha Volume 13 came out, it became apparent that they were looking to win the war.

The book dropped at Tokyopop size, yes, but also with a radically redesigned book-cover treatment, cutting edge for comics at the time. AND it landed at just $8.95, a buck cheaper than the new $9.99 standard. Take a look, side by side, at the covers of Inu Yasha 2 first edition and new edition… It was like Viz had finally woken their design dept. up out of the 1980s, and were ready to COMPETE:

Slick, eh?

But this was just the harbinger. You see, Inu Yasha Volume 13 was the first new Viz manga to be released in the new format, but Viz hadn’t decided to just move forward with this new format. No, they were moving backwards as well, and Viz had (and still has) the largest manga backlist in the industry. Inu Yasha Volume 13 started a tidal-wave; a flood. A flood of what immediately became known as “Old Format Viz”.

“Old Format Viz” was basically the comics equivalent of herpes: no one wanted it, but chances are everyone had it, in one form or another, and would try anything to get rid of it.

“But wait,” you ask. “Why would everyone try to get rid of differently-sized printings of perfectly good manga, some of which was even released the very-same-month as Inu Yasha 13?” That’s a very good question. The answer is simple: I’m a bit of an unreliable narrator.

Y’see, Inu Yasha Volume 13 was solicited in January of 2003 and it was the first manga to be solicited in the new format, and it was the first brand new Viz manga to be released in the new format. But a few weeks before it appeared in stores, Viz had rush-solicited and then released this:

FEB03 2196 DRAGONBALL VOL 1 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2197 DRAGONBALL VOL 2 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2198 DRAGONBALL VOL 3 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2199 DRAGONBALL VOL 4 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2200 DRAGONBALL VOL 5 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2201 DRAGONBALL VOL 6 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2202 DRAGONBALL VOL 7 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2206 DRAGONBALL Z VOL 1 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2207 DRAGONBALL Z VOL 2 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2208 DRAGONBALL Z VOL 3 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2209 DRAGONBALL Z VOL 4 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2210 DRAGONBALL Z VOL 5 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2211 DRAGONBALL Z VOL 6 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

FEB03 2212 DRAGONBALLZ VOL 7 TP 2ND ED (C: 3) $7.95

Viz had announced that it wouldn’t just be their new books, going forward, that would be in the new format. They’d be going back to press on more-or-less their entire backlist over the next 24 months, and re-releasing it all in the new format, at a new pricepoint of between $8 and $10! A new pricepoint that was between 33% and %50 cheaper than the previous versions had been, in a more popular, better-designed format. They released 14 volumes of Dragon Ball and Dragon Ball Z manga on the same day, then, the single-largest release of English language manga at the same time in the history of the medium. Oh, and Viz had basically just bricked all of their existing stock on store shelves.

The people who suffered the most? Direct Market comic book stores who were buying the product non-returnably from Diamond. You see, if Borders or Barnes & Noble stopped selling the old format Inu Yasha volumes because it was now being released in a shiny new edition for half the price, they could just send the one that didn’t sell back to Viz and get a refund. Direct Market stores, who had stocked and sold manga for years? Almost all of their Viz product was ‘dead’. Overnight. They were not happy, Diamond wasn’t going to take the product back, and Viz never offered. Even at phenomenally deep discounts (and really, they STARTED at 50% off on Old Format Viz), most buyers didn’t care, they didn’t want the books that “didn’t match” the rest of their collections. Manga fans are both fickle and OCD; it’s a deadly combination. If you were an optimist-type retailer, you looked at it as a long-haul thing, clearing out shelf-worn copies of books and improving the overall health and longevity of manga in your store, even if it cost you a bunch of money. If you were a pessimist, you stopped carrying manga.

Actually, heh, you shoulda heard the Ranma 1/2 fans who were more than half-way through the series in the Old Format before being told, flat-out, that the series would _not_ be finished in that format and that they’d have to switch to the new one. And re-buy 20 or 21 volumes of a book that they’d already spent nearly $400 collecting if they wanted the spines to match up. Sucks to be a Ranma fan. Or an OCD one anyway.

In the first 3 months of the Viz revamp, Viz had re-released nearly 40 volumes in new editions, and changed over the vast majority of their line to the new Tokyopop format. The only hold-outs were series that would not be getting reprints, like Kia Asamiya’s Steam Detectives, or mature works and special projects like Vagabond by Takehiko Inoue. The writing was on the wall: the old format books were dead, and you were only hanging onto them until the new ones came out. If that long.

In the end of course, the format was a godsend and we all made so much fucking money off those books over the last decade. As this was happening, I had started working at The Beguiling and doing some of the ordering and shelving, including these books, and was just marvelling with every announcement about the interesting times we lived in. I even picked up all of the Dragon Ball volumes, now that they were uncensored again, to treat myself.

And it all started (more or less) with Inu Yasha, the harbinger of the most massive change that manga saw in the last decade: the move en masse to cheaper, more attractive formats that changed the way we look at comics. Tokyopop may have invented it, but Viz used it better.

-o+O+o-

Tomorrow: Parts 5 & 6!

– Christopher

Great picks again, Chris! Regarding the “Tokyopop format,” while it doesn’t correspond to any trim size in Japan, it is exactly the same trim size used for most boys Manhwa in Korea. They also print a lot of localized editions in that format. The dimensions are a pretty decent compromise between the most common A4 and B4 paper sizes used in Japan, longer/thinner than B4, wider than A4. (scaling A4 up to B4 dimensions or vice versa would require even more cropping or awkward gutters). At this point, the uniform trim size might seem like an unnecessary compromise, but at the time, it made possible the Point-of-Purchase and standup displays, secure uniform shelving space and I think had a strong appeal for the collector mentality with its tidy uniformity. Retailers and fans both responded very positively to a change from the highly erratic sizes in the traditional comics shelves. I’m just glad that publishers can now shake up the format with fancy new packaging and trims like Viz’s sexy Sig size. Maybe it was the early ’00s industrial design trend that preferred uniformity whereas now we like our funky edges?

re: above, I am slightly stupid regarding trim sizes. I don’t think I mean A4. I mean whatever the 17.2 x 11.2 trim size is called in Japan — the aspect ratio that most shonen/shojo manga are printed at as opposed to the wider trim used for seinen. I’m sorry — it’s been so long since I worked on that side of things. If you can get digital materials or film for the books being reproduced, the artist’s original bleeds allow for more wiggle room when resizing, but unfortunately that wasn’t always (read, seldom was) an option, so using a trim size that required little cropping was key.

Ah, man, now you’ve made me want to come out of retirement just to an updated comparison of a towering stack of a dozen Shonen Jumps vs. a measly pile of fifteen American comics.

The 5.5×7.5 Tokyopop format was chosen because it corresponds to the size and ratio of a standard DVD case — allowing the manga to be slotted into existing fixtures at outlets like Suncoast without retrofits.

In turn, the DVD case is the width of a CD jewel box, and as tall as a old VHS tape — which is also obvious, as the actual discs inside are the same size, though the added height is less obvious but necessary when you consider retailers of DVDs were slowly converting formats and needed merchandise that would co-exist well — and that didn’t require an outlay just for new shelves. (the same goes for retailers adding DVD video to older music departments)

Protip: if you’re a startup comic shop and you were looking for fixtures to merchandise manga, maybe you should check into the CD bins & DVD shelves that might be had for cheap from music & video stores going out of business.

That is an excellent point about the size of the DVD cases, and one I’d forgotten. Thanks, Matt.

Dark Horse’s editions of Astro Boy were actually the same size as the old Pocket Mixx graphic novels or standard shonen/shoujo tankobons.

Also, the Viz Signature size is the old Viz graphic novel size. Vagabond is an interesting case since it has undergone three edition changes so far from Viz Comics to Editor’s Choice, to “flower” Signature. The solicitations still show the older Signature logo, but I wouldn’t be surprised to see the new “SIG” logo pop up on the latest volume.

The nearly identical height to a DVD and ability to repurpose those shelves certainly contributed to Tokyopop’s choice, and absolutely helped the success of the format, but it was largely serendipitous and hardly the driving reason. Prior to the 100% Authentic campaign, Tokyopop matched aspect ratios (if not trim sizes for the larger books) with the Japanese originals. When we published the first Korean manwha, Island, in TPB, it followed that tradition. In fact, it was a 1-to-1 match (like the “pocket Mixx” books) with the Korean original. That size happened to be 5 x 7 7/16. When the decision was made to move to unflipped, cheap editions, originally, they were going to follow the A4/Pocket Mixx size. Some of us didn’t like the smaller format, whether for aesthetics or because of perceived value, so in looking for a new uniform trim, we ended up going with the Korean trim size, yes because of the DVD similiarity, but also because it was a “Goldilocks” compromise (not too big, not too small) with a precedent as a 1-size-fits-all aspect ratio. Fun fact, the Tokypop trim was, at least for the first few years, 5 x 7 7/16ths. I don’t know when that was rounded off to the much saner 7.5, but you can definitely tell the difference when lining up old Tokyopop books next to current manga digest books.