One of the things that I mentioned on the Inkstuds podcast with David, Brandon, and Robin, is an idea that’s been rattling around in my head for a long while now, and that’s the concept of the comics industry (and occasionally the medium) going out of its way to ‘other’ the success of books that they don’t like, or don’t want to be representative of ‘their’ industry. (If you’re not familiar with the term Othering, btw, this is a pretty good description.) I want to dig into that idea a bit more, because I think we’ve maybe just witnessed a real shift in the way the industry is able to deal with those successes.

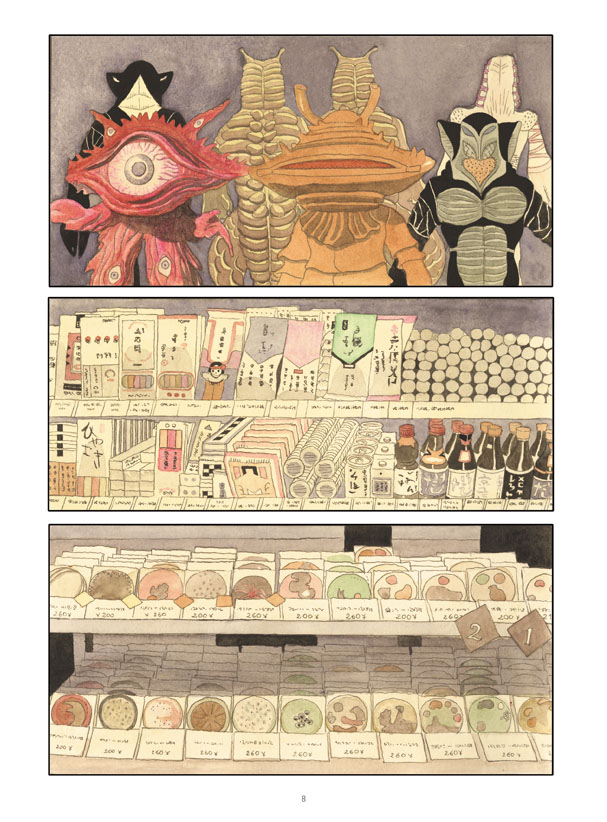

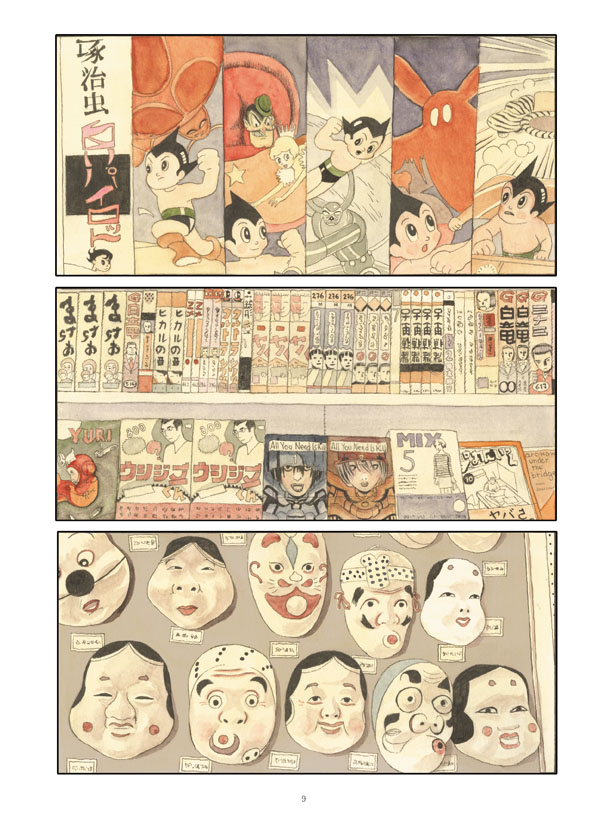

So, basically, my theory goes that the manga boom in the late 90s sort of blew up every single thing that the industry thought about comics, and who the audience is for comics, and what comics can do. I’ve been writing about comics on and off since about 96-97, and I’ve been writing not only about the potential for comics, but then the realization of comics. It was a time of really quick change, a lot of it good change, sparked mostly by $10 trade paperbacks of Sailor Moon (big-ups to Tokyopop). The success of those books and the ones that followed like Card Captor Sakura, Peach Girl, Fruits Basket, and so many more, were the proof to the theories that comics could be for everyone, for women and for girls especially, and could sell in numbers that were comparable to how they sold overseas. Then Viz launched Shonen Jump, Random House launched the Del Rey Manga line (now Kodansha), Hachette launched Yen Press. The comics came out, the comics sold well, the comics brought in new audiences. Sales exploded, sales leveled, sales crashed, sales leveled again, and just this year everyone’s saying that sales are up a little once more. Not just for girls and women, but across the board. This is all stuff that actually happened, and you can go back and look it up if you don’t want to take my word for it.

So how did the rest of the comics industry react to this sea-change? In the pettiest way possible of course, by othering the success of that material as much as they could. “Manga aren’t comics,” went the discussion. They were, and are in many ways, treated as something else. The success that they had, the massive success that they continue to have, doesn’t ‘count’. All those sales and new readers were just ‘a fad’, and not worthy of interest, respect, or comparison to real comics. It was the one thing that superhero-buying-snobs and art-comics-touting-snobs could agree on (with the exception of Dirk Deppey at TCJ, bless him): This shit just isn’t comics, real comics, therefore we don’t have to engage it. You can see traces of this attitude, in, for example, The New York Times Best Sellers list for comics, which split manga out into its own category after pressure from non-manga publishers, because the lists woulda been manga-dominated every week. Then the manga boom and manga bust and leveling could all happen off to the side, and no one would have to encounter scary ideas like “women make comics” and “women read comics” and “women buy comics” and they could keep the now-more-narrowly-defined comics industry the exact shape that they wanted to, albeit a little smaller and a little sadder for the exclusion.

(Side note: Sadder still than the people who insist(ed) that manga aren’t and can’t be comics are the poor brainwashed weebs who insist that comics can’t be manga. It’s a dumb argument. If comics is a language then manga is at most a dialect, at least slang, not a different language entirely.)

(Side note 2: At least alt-comix finally embraced manga to a degree in the mid 2000s. Although the gender split among creators of manga translated into English and published by alt-manga publishers is about 90% men at this point, which is not really very good!)

So, the comics industry was able to successfully ignore the massive success and new audiences that the manga publishers brought with them. But you know who didn’t? Kids publishers. Scholastic Graphix. Papercutz. Abrams. First Second. Kids Can Press. Even Yen Press’ arm at Hachette. They saw that with the right conditions, you could get someone other than males aged 18-49 to read comics, and have it be incredibly successful. These publishers paid attention and put together imprints to publish original work specifically for the audiences that the comics mainstream insisted didn’t exist: Kids, girls especially, tweens and teens. And the books sold well. Won new audiences. A whole industry of “original graphic-novel” based creation sprung up that simply did not exist before the success of manga, the success of Bone at Graphix, of Twlight: The Manga at Hachette, Nancy Drew & Hardy Boys graphic novels, Binky the Space Cat, Diary of a Wimpy Kid, American Born Chinese. Or Smile, by Raina Telgemeier. Smile, which sat on the bestseller list for a year and was largely disregarded by the comics industry. Incredible bestsellers, many with outside-of-comics media attention, largely ignored, deliberately ignored. Because their success didn’t fit the paradigm. They weren’t comics. They were ‘for kids’.

(Side Note 3: Still heard the old saw that ‘Kids Comics Don’t Sell’ at Comic-Con this year from a larger pub.)

“Those aren’t real comics, aren’t real graphic novels,” went the refrain around 2010, 2011. “They’re for kids. They lack sophistication, they lack nuance, they’re babyish.” So you can ignore the massive success of Bone and Smile and 66,000 copies of Twlight: The Manga sold on release week, or a 190,000 copy print run on Papercutz’ Lego: Ninjago graphic novel, because the books, if kids are reading them, can’t possibly be any good. Because the books in a publisher’s line are all the same trim size, there’s no art to them. Because they sell well, there’s no art to them. Regardless of who is creating them or under what circumstance. It’s a garbage argument that, once spelled out here becomes obvious and sad, but it’s still an argument that gets made all the time, with every book release. And we can successfully other, again, the success of books aimed at anyone who isn’t a male aged 18-49, and the industry puts even tighter blinkers on and it gets a little smaller, and a little sadder still.

(Side note 4: Raina Telgemeier wasn’t considered ‘notable’ enough by Comic-Con to be a Special Guest at Comic-Con in 2014–even though SMILE and DRAMA had topped the NYT Best Seller lists for more than a year each, at that point. They realized the error of their ways this year and she was a special guest for 2015.)

Speaking of 2015… here we are. The past 20 years have been specifically depressing when it comes to how the comics industry, particularly what we think of as ‘mainstream’ comics and ‘art-comics’, have regarded the massive changes that have been happening in the larger medium of comics and graphic novels, and their perception and place in North America. It’s not all bad, there are some bright spots at traditional comics publishers when it comes to representation, diversity, and audience… but I think it’s mostly bad. But I also think that this year, 2015, is gonna pretty much put the nail in the coffin for the old way of thinking, because the ‘othered’ books, and the audiences for those books, and the creators of those books, are dominating any real discussion of the medium AND the industry, and the folks who haven’t gotten with the program look foolish as hell.

The optimism started for me earlier this year. The Tamaki’s This One Summer co-published by Groundwood and First Second Books took home the Printz Award and the Caldecott Award (among many other honours), a very big deal. Only the second time a graphic novel and won the Printz and the first time for the Caldecott. These were good, solid wins, that caused delightful controversy in library circles. Brought a smile to my face.

Last month Scholastic Graphix sent out a seemingly innocuous note that was actually a very loud statement: Congratulations to Raina Telgemeier for Smile being on the NYT Bestseller list for three straight years–oh and she’s also got the top four spots on the list simultaneously as well.

It was, as the kids say, shots fired. Scholastic e-mailed this graphic to the press of the entire comics industry, and they wanted to say something very clear: “This isn’t a flash in the pan, this isn’t ‘just’ kids books, this is a writer-artist who has made a major achievement, who has won a huge audience and continues to win new audiences every single week, with every single book she makes. Pay attention.”

Flash back to a little over a week ago: This is the first year that Marvel Comics as a Publisher did not win any Will Eisner Awards for excellence in comics, and none of the creators who won individual awards like penciller, writer, inker, colourist (awards that were basically invented to recognize achievements by creators working on assembly-line big-two superhero books) had any substantial Marvel comics work this year. DC Comics’ recognition came for J.H. Williams III’s work on Sandman: Overture and a month’s worth of Darwyn Cooke variant covers, which is a very small showing for them. You know who did take home Eisners though? A lot of women, a lot of folks working on books with large or primary female audiences, and young audiences too. Emily Carroll, Evan Dorkin & Jill Thompson, Shannon Watters & Grace Ellis & Noelle Stevenson & Brooke A Allen of Lumberjanes, Ariel Cohn & Aron Nels Steinke, Cece Bell, Mariko Tamaki & Jillian Tamaki, Gene Yang, Raina Telgemeier, Fiona Staples, they took home Eisners this year.

The 2015 Eisner winner list doesn’t look like other years, and even though the list has been trending in this direction for a few years, it was surprising to me. I smiled pretty hard at that one. The Eisner Awards are voted on by professionals working in the comics industry, and it’s pretty clear from the results that the professionals working in the comics industry AND the books that they think best represent the industry to the outside world have changed dramatically from even five years ago, to be considerably broader, and considerably more diverse.

(Side Note 5: I want to be clear: I specifically do not intend to denigrate the work of anyone nominated for an Eisner this year who didn’t win, either in my personal appreciation of their work or the larger recognition of their work. It’s intended to illustrate a larger shift in how Eisner voters are approaching the awards, and who the voters now are. Just needs to be said.)

I’ve been thinking about those Eisner wins for the last week, about Raina’s success, and about some great, important conversations I had at Comic-Con, and I can’t help but grin about it. Things aren’t just changing; things have changed. I think very much for the better. We are at a point where the success of traditionally ‘othered’ books and authors is so large, so in-everyone’s-face, and so displacing of traditional comics ‘successes’, that you simply can’t reduce the size of the industry enough, or tighten the blinders enough. You can’t other what has become the majority.

What finally prompted me to talk about this, to expand a couple of short sentences in the podcast into a blog post was actually this week’s New York Times Best Seller list for comics. The softcover list features female creators as 9 of the top 10 books (with a very women-audiences-friendly holdout by lovely male creators). The folks on my Twitter timeline had a nice little celebration when that list was released, and I’m really happy for them. Well, not really ‘them,’ actually. But us. All of us, including the superhero pubs and the art-comix pubs and even the sour fans and weebs; the industry is markedly, demonstrably better for more people right now than it has been in years, because we can produce successful books for women and men, for children, tweens, teens, and adults, and those books can sell, and we can celebrate our successes together, if we want to. We get more, different, successful comics. That’s a win.

The NYT list and the Eisners and basically every single benchmark we have in this industry are flawed, often badly flawed, but we can take all of these things together and pull out some very clear and important trends: We as an industry have made enormous steps in the last 20 years to not deliberately exclude women and young people from the comics medium, and to actively celebrate their accomplishments. That doesn’t mean that everyone is now suddenly enfranchised, or that the industry is done deliberately excluding audiences (not to mention creators, not to mention people working in the publishing industry), but real progress has been made.

Let’s recognize it. Let’s celebrate it. Most importantly, let’s keep it going, and keep pushing for positive, inclusive change.

– Christopher